1. Permissions via Bitwise Flags

First we need to know the meaning of the following bitwise flags:

So a number 6 = 4 + 2 means READ and WRITE, which is also represented by O_RDWR in C.

Usually a permission to a file is represented by the combination owner-group-usr format, for example:

In mac this number is actually owner-staff-others, we can check all the groups in our system via command groups, by which I get

All the users that can log into this mac machine are classified into staff. The following are not of group staff:

root(superuser) - in wheel groupnobody- unprivileged account_www- web server user_mysql- database user_spotlight- spotlight indexing_windowserver- window server process- And many other

_prefixed system accounts

2. ls -l

ls -lNow an ls -l (l stands for long format) command to a file gives

Which shows that this file has mode number 0644, with the group staff being 4 and with other matadata.

In C we cannot omit 0 as it tells the compiler this number is in octal format.

But in other linux command such as chmod 644 some_file.sh the omission is acceptable because the command is written smart enough to assume octal when you give it a 3-digit number.

Files downloaded from the internet are by default 0644. That's why sometimes we need to explicitly execute chmod 0744 to make a script executable.

3. Formatting in VSCode

In settings.json:

4. List in C

We can declare an array in either way:

In mose cases list (an array in the second line) will be decayed to a pointer, the commonly used expression list[2] actually means:

5. Compile Modules

5.1.Intermediate Object Files

Intermediate Object Files

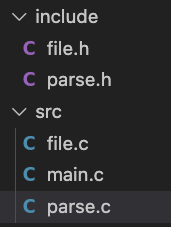

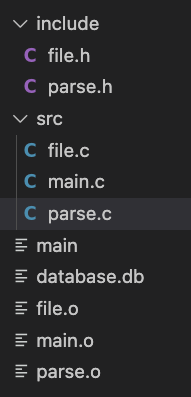

Consider the following project structure:

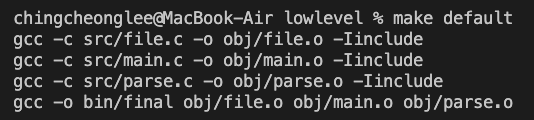

We compile intermediate object file one by one by:

Here by the flag -c (compile only), we ask gcc to stop after compilation stage and don't do the linking.

By linking we mean: The final stage that combines multiple object files (.o) and resolves all references to create an executable.

What linking does:

-

Combines object files - merges

main.o,utils.o,logger.ointo one executable -

Resolves symbols - connects function calls to their actual implementations

-

Includes libraries - links standard library functions (printf, malloc, etc.)

-

Fixes addresses - determines final memory addresses for functions and variables

5.2.Compile Modules into an Executable

Compile Modules into an Executable

We repeated the step above 3 times:

Then we obtain all object files:

Create a bin/ directory and combine all the object files into one binary:

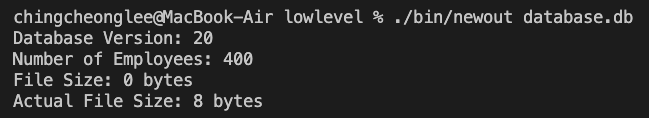

Now we test the binary and obtain:

6. Makefile

The steps in 〈5.2. Compile Modules into an Executable〉 can be further simplified by Makefile and Pattern Rules.

-

default,clean, etc are called rules, they are executed viamake(equivalent tomake default),make cleanetc -

$(TARGET)is called a make variable -

defaultrule is now asked to execute the$(TARGET)rule, this is simply a rule that has a variable name -

When

$(TARGET)rule is being executed:-

By definition

$(TARGET): $(OBJ)means$(OBJ)is a dependency (list) of$(TARGET)rule; -

It tries to find whether the object file in

$(OBJ)exists, if not it tries to find any pattern rule that match files in$(OBJ); -

Pattern rule

obj/%.ogets executed repeatedly; -

When all pattern rules are done,

$(TARGET)rule goes further togcc -o $@ $?, where$@is the target name, and$?$is a name in$(OBJ);

-